A diagnosis of dementia deeply affects each and every one it touches, reaching beyond the individual affected.

Through awareness, education and support, it’s our mission to help improve the quality of life for those affected by dementia – not only the individuals, but also their main support person, whānau and support networks. All services provided by Dementia Auckland to the Auckland region are free of charge. The Dementia Auckland team is committed to ensuring that the right support, advice and information are available at the right time.

Dementia Auckland Support Desk

0800 433 636

Monday to Friday 8:30 am – 4:30 pm. Closed weekends and public holidays. In an emergency or crisis please call 111, or your local Health Board.

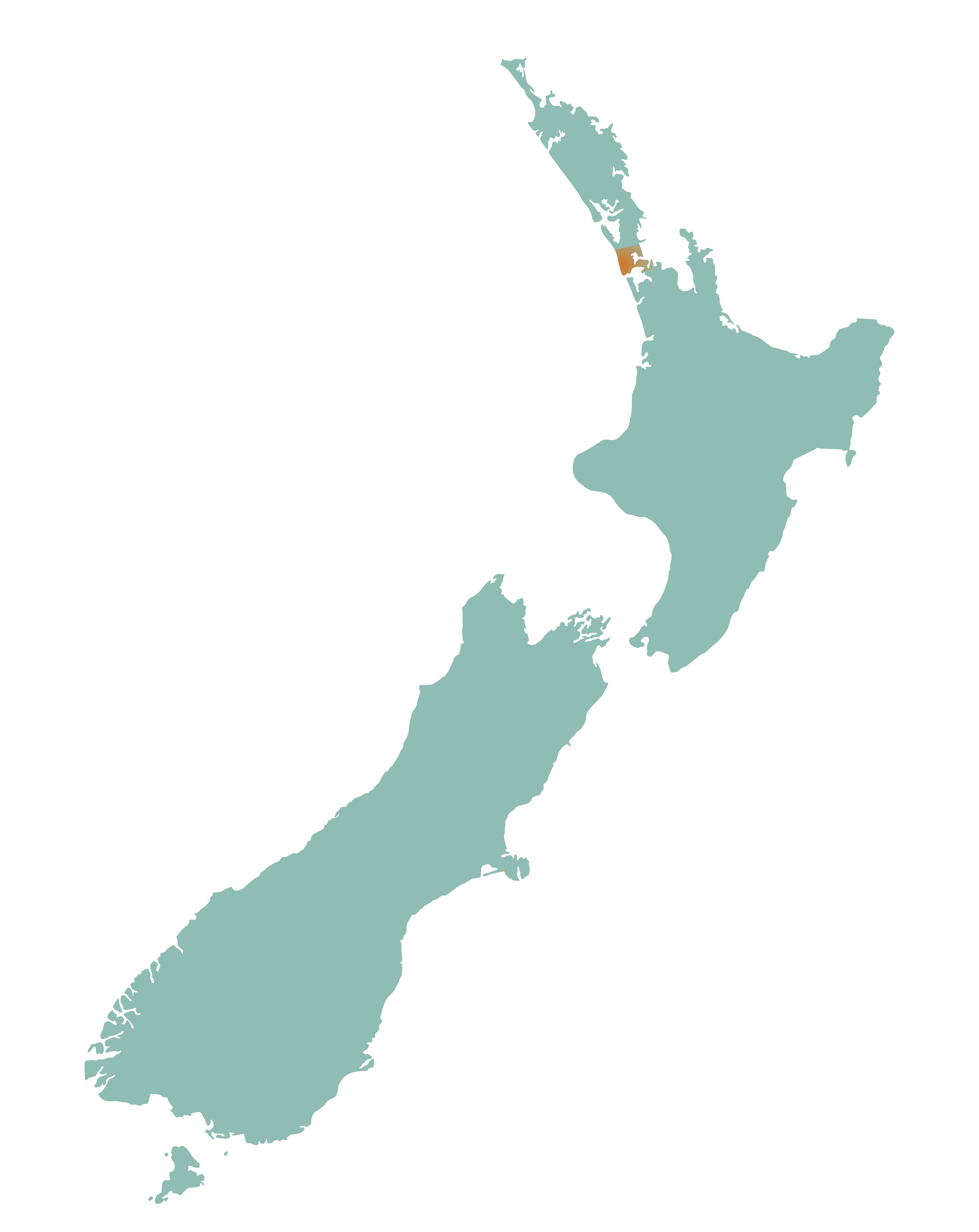

Dementia Auckland Support Area